Template:Short description Template:Infobox film

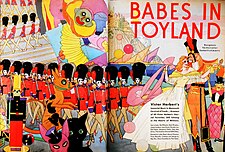

Babes in Toyland is a Laurel and Hardy musical Christmas film released on November 30, 1934. The film is also known by the alternative titles Laurel and Hardy in Toyland, Revenge Is Sweet (the 1948 European reissue title), and March of the Wooden Soldiers (in the United States), a 73-minute abridged version.

Based on Victor Herbert's popular 1903 operetta Babes in Toyland, the film was produced by Hal Roach, directed by Gus Meins and Charles Rogers,[1] and distributed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. There are two computer-colorized versions between The Samuel Goldwyn Company in 1991 and Legend Films in 2006.[2]

Although the 1934 film makes use of many of the characters in the original play, as well as several of the songs, the plot is almost completely unlike that of the original stage production. In contrast to the stage version, the film's story takes place entirely in Toyland, which is inhabited by Mother Goose (Virginia Karns) and other well-known fairy tale characters.

Plot

Stannie Dum and Ollie Dee inhabit a shoe residence alongside Mother Peep, Bo Peep, and a diverse array of children. Their tranquil existence is disrupted by the malevolent Silas Barnaby, who harbors intentions to wed Bo Peep and seize control of their shoe abode through foreclosure. Faced with imminent eviction, Ollie impulsively offers their meager savings to stave off the threat, unaware that Stannie has squandered the funds on peewees.

Subsequent attempts to procure the mortgage funds from their employer, the Toymaker, result in calamity when a misguided toy order leads to chaos in the toy shop, resulting in their dismissal. In a desperate gambit to thwart Barnaby, the duo embarks on a futile burglary endeavor, culminating in their arrest and sentencing to banishment in Bogeyland. Despite Bo Peep's reluctant agreement to Barnaby's demands to spare their lives, Stannie and Ollie endure a dunking and face impending exile.

Employing guile and resourcefulness, Stannie and Ollie devise a cunning scheme to disrupt Barnaby's machinations during Bo Peep's wedding ceremony. By unveiling Stannie in Bo Peep's bridal attire, they expose Barnaby's treachery and obliterate the mortgage, thus freeing Bo Peep.

However, Barnaby exacts vengeance by framing Bo Peep's true love, Tom-Tom, for "pignapping," leading to his unjust banishment to Bogeyland. In a race against time, Stannie and Ollie unravel Barnaby's scheme, ultimately rescuing Tom-Tom and exposing Barnaby's villainy to the townspeople. A climactic confrontation unfolds in Bogeyland, where Tom-Tom valiantly defends Bo Peep from Barnaby's advances, while Stannie and Ollie join the fray to repel the Bogeymen. The film crescendos with the triumphant march of the wooden soldiers, orchestrated by Stannie and Ollie, driving back the Bogeymen and vanquishing Barnaby, restoring peace to Toyland.

As the kingdom celebrates its salvation, a comedic mishap ensues when Stannie and Ollie inadvertently bombard Ollie with darts from a malfunctioning cannon.[3][4][5]

Cast

- Virginia Karns as Mother Goose

- Charlotte Henry as Bo-Peep

- Felix Knight as Tom-Tom Piper

- Florence Roberts as Widow Peep

- Henry Brandon as Silas Barnaby

- Stan Laurel as Stanley "Stannie" Dum

- Oliver Hardy as Oliver "Ollie" Dee

Uncredited cast

- Frank Austin as Justice of the Peace

- Billy Bletcher as the Chief of Police

- William Burress as the Toymaker

- Russell Coles as Tom Tucker

- Zebedy Colt as Willie the Pig

- Alice Dahl as Little Miss Muffet

- Jean Darling as Curly Locks

- Johnny Downs as Little Boy Blue

- John George as Barnaby's Minion

- Sumner Getchell as Little Jack Horner

- Pete Gordon as The Cat and the Fiddle

- Robert Hoover as Bobby Shaftoe

- Payne B. Johnson as Jiggs the Pig

- Alice Moore as the Queen of Hearts

- Kewpie Morgan as Old King Cole

- Mickey Mouse as Himself

- Ferdinand Munier as Santa Claus

- Charley Rogers as Simple Simon

- Angelo Rossitto as Elmer the Pig

- Tiny Sandford as Dunker

- Marie Wilson as Mary Quite Contrary

Songs

Template:Unreferenced section The film features only six musical numbers from the enormous stage score, though that is fitting for a musical with only a 78-minute running time. Included in the film, in the order in which they are performed, are: "Toyland" (opening), "Never Mind Bo-Peep", "Castle in Spain", "Go to Sleep (Slumber Deep)", and "March of the Toys" (an instrumental piece).

Also included in the film is an instrumental version of "I Can't Do the Sum" for the running theme of Laurel and Hardy's scenes. Another song, "Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?", is not one of the original stage songs but appears in the Three Little Pigs segment, heard only as an instrumental piece.

The opening song is performed by Mother Goose and an offscreen chorus; most of the others are sung by Bo Peep and/or Tom-Tom. While none of the songs is performed by Laurel and Hardy, the two briefly dance and march in a memorable scene to "March of the Toys".

Production

RKO Pictures originally purchased the rights in 1930 with the plans of filming the musical partly in two-strip Technicolor. Plans were announced to have Bebe Daniels (later Irene Dunne) star in the musical along with the comedy team of Wheeler and Woolsey. Due to the backlash against musicals in the autumn of 1930, the plans were dropped. A couple of years later, some thought was given to filming the musical as an animated feature film to be shot in Technicolor by Walt Disney, however, the projected price of the film gave pause to RKO's plans. Hal Roach, who had seen the play as a boy, acquired the film rights to the project in November 1933.[6]

The film was completed in November 1934. The village of Toyland was built on sound stages at Hal Roach Studios with the buildings painted in vivid storybook colors, leading Stan Laurel to regret that the film wasn't shot in Technicolor.[7] The film was originally produced in sepia tone and later colorized.

Walt Disney personally approved the appearance of Mickey Mouse in the film along with the use of the song "Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?".[8]

Reception

Critics' reviews were positive. Andre Sennwald of The New York Times called the film "an authentic children's entertainment and quite the merriest of its kind that Hollywood has turned loose on the nation's screens in a long time."[9] Variety proclaimed it "a film par excellence for children. It's packed with laughs and thrills and is endowed with that glamour of mysticism which marks juvenile literature."[10] John Mosher wrote in The New Yorker: "It's certainly far more successful than was last year's Alice in Wonderland, and the children will probably be far less bored by it than they generally are by those films designed especially for them".[11] Film Daily called it "delightful musical fantasy" and "dandy entertainment".[12] The Chicago Tribune review read: "It's been many a long day since I've had so much pure (and I MEAN pure!) fun as I had watching this picture".[13]

Babes in Toyland, one of many feature films with Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy, was also popular at the box office.[14] However, many years laterTemplate:When in a filmed interview, Hal Roach admitted that on its first release, the film lost money. After it appeared in theaters, it was re-released several times with the title constantly changed, to make it seem to audiences that they were going to see a different film. It surfaced as a holiday movie on TV as March of the Wooden Soldiers, where it was rerun annually on some local affiliates for many years. On one local Atlanta station, the film was shown as a Thanksgiving special only a few weeks before the release of its 1961 Disney Technicolor remake, so that those who saw it on television and then saw the Disney film version over the Christmas holiday had the experience of seeing two different versions of the same work, within a few weeks of each other.

A holiday staple, this film was shown by many television stations in the United States during the Thanksgiving/Christmas holiday season, each year, during the 1960s and 1970s. In New York City, it continues to run (as of 2024) on WPIX as March of the Wooden Soldiers, airing on that station in the daytime on Thanksgiving Day and Christmas Day. It also runs nationally, on occasion, on This TV, as well as Turner Classic Movies.[15]

Copyright status

The original 79-minute film is under copyright to Prime TV Inc., the assets of which as of the present time are owned by television station WPIX (and its current owners, Mission Broadcasting), with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (under Orion Pictures, which like MGM is now part of Amazon) still handling partial distribution rights of the film, making this one of the few films that were not part of MGM's pre-May 1986 library which Ted Turner purchased it.

In 1950, a 73-minute edited version was distributed by Lippert Pictures, retitled March of the Wooden Soldiers; it was released without a copyright notice. The edited version of the film had the opening tune "Toyland" trimmed and the "Go to Sleep (Slumber Deep)" number cut completely. Also removed were Barnaby's attempted abduction of Little Bo-Peep and his ultimate fistfight with Tom-Tom.[16] March of the Wooden Soldiers has been distributed by many motion picture and home video companies over the decades, as if it were in the public domain;[17] however, because it relies entirely on copyrighted material from the 1934 film, March of the Wooden Soldiers itself falls under the same copyright as its parent film and will not truly enter the public domain until that film's copyright expires in 2030. WPIX has not enforced its copyright on March of the Wooden Soldiers, effectively making the film an orphan work.

History

Hal Roach first sold the film in 1944 to the Victor Herbert estate, and at this point, the film’s copyright was reassigned to Federal Films. Shortly thereafter, the rights reverted to film partners Boris Morros and William LeBaron. In 1948, film producer Joe Auerbach acquired the picture and leased most of his distribution rights to Erko, and it was beginning with this distribution deal that the film began to be edited down to alternate versions, in this case, a 75-minute revised reissue. By 1950, Lippert Pictures acquired some distribution rights, and as aforementioned, cut the film further to 73 minutes. Later in the 1950s, television rights were licensed to Quality Pictures, and by 1952 TV rights reverted to Peerless Television Productions.

New York TV station WPIX’s long association with the film began with its initial airing on December 24, 1952, and it has aired almost annually ever since. Meanwhile, by 1968, Prime TV Films would acquire ownership of the film, and as previously mentioned, they have been the copyright holders of the film ever since. In the 1970s, Thunderbird Films released 16mm prints drawn from a heavily spliced (and incomplete) master. In the 1980s, WPIX and its then-owner, Tribune Broadcasting, leased the film to The Samuel Goldwyn Company. The Samuel Goldwyn Company's select holdings (particularly the non-Samuel Goldwyn-produced films) ultimately became part of the Orion Pictures library. Finally, Orion became a division of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, thus after nearly eight decades, bringing partial rights full circle. Since 1984, the underlying rights to the film have been the property of WPIX and its successive owners.[18]

In 1991, the complete film was restored and colorized by American Film Technologies for television showings and video release by The Samuel Goldwyn Company.[19][20] In 2006, the complete print was again restored and colorized by Legend Films, using the latest technology.[19][21][22] Although the Legend Films release was advertised under its reissue title, both the color and black-and-white prints featured the original title and opening credits.[21][23]

See also

- List of Christmas films

- List of films with a 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, a film review aggregator website

- Parade of the Wooden Soldiers

References

Citations

General sources

- Template:Cite book

- Everson, William K. The Complete Films of Laurel and Hardy. New York: Citadel, 2000, (first edition 1967). .

- Louvish, Simon. Stan and Ollie: The Roots of Comedy. London: Faber & Faber, 2001. .

- McCabe, John. Babe: The Life of Oliver Hardy. London: Robson Books Ltd., 2004. .

- McCabe, John with Al Kilgore and Richard W. Bann. Laurel & Hardy. New York: Bonanza Books, 1983, first edition 1975, E.P. Dutton. .

- McGarry, Annie. Laurel & Hardy. London: Bison Group, 1992. .

External links

- Template:IMDb title

- Template:Internet Archive film

- Template:TCMDb title

- Template:AFI film

- Template:Rotten Tomatoes

Template:Laurel and Hardy filmography Template:Charley Rogers Template:Gus Meins Template:Authority control

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Everson, William K. 1967. The Complete Films of Laurel and Hardy. Citadel Press. p. 160.

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Barr, Charles. 1968. Laurel & Hardy. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 90. Template:OCLC

- ↑ p. 150 King, Rob Hokum!: The Early Sound Slapstick Short and Depression-Era Mass Culture Univ of California Press, 7 Apr. 2017

- ↑ p. 128 Rowan, Terry Character-Based Film Series Part 3 Lulu.com

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite magazine

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Churchill, Douglas W. The Year in Hollywood: 1934 May Be Remembered as the Beginning of the Sweetness-and-Light Era (gate locked); New York Times 30 Dec 1934: X5. Retrieved December 16, 2013.

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Skretvedt, Randy. 2023. March of the Wooden Soldiers: The Amazing Story of Laurel & Hardy’s “Babes In Toyland”. Bonaventure Press. p. 472-515.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite news